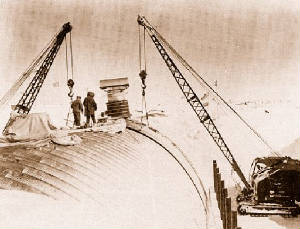

800 miles from the North Pole, in the middle of the cold war, in the Greenland Ice sheet, America was building. Lashed daily by winds of up to 200 km/h the US Army Corps of Engineering slowly dug out their trenches and sunk in the buildings. In October 1960 they were finished, Camp Century was habitable. The city beneath the ice.

Camp Century was built as an ‘Army Polar Research and Development Center’. Due to the remote location it was powered by an Alco PM-2A, the world’s first portable, and working nuclear reactor. Additionally Camp Century had a Barbershop, Library, Standby Diesel Power Plant and Theatre. That is more than a science outpost needed, but science was not the aim of the project.

The initiative was codenamed ‘Project Iceworm’. A United States plan to embed a vast network of tunnels into the Greenland ice sheet. The small tunnels branching from Camp Century would hold up to 600 nuclear warheads. A geographical expedition commissioned in 1958 said the plan was viable so they began with Camp Century in 1960.

At this time a new type of intercontinental ballistic missile dubbed ‘Iceman’ had been invented. It was capable of carrying nuclear warheads to anywhere within around 5,500 kilometres. They would be stored in the extra tunnels which would run from the camp up to the surface. In an emergency they could be launched, raining thermonuclear justice upon any offending Communists. Those tunnels were not constructed.

The largest of the 21 tunnels in the camp was called ‘Main Street’. Over 300 metres in length, 8 metres wide and 8.5 metres high, it was deeply impressive. All of the tunnels were covered with arched, corrugated-steel roofs and were lined with lights which never turned off. There was a problem though. The ice sheet was too active. To stop the ice crushing camp it had to be regularly trimmed.

In the first year, up to 1961, the average of 200 staff took measurements. The scientists took what they thought were useless ice cores from the glacier using a combination of thermal and electromechanical drills to reach the bottom of the Greenland Ice Sheet. The true value of the ice cores gathered was not realised until many years later. The value of Project Iceworm was concluded in 1961 however. The ice was too active, the small tunnels for missiles wouldn’t be stable enough for long enough. The plan was abandoned.

The camp was expected to last for at least 10 years, but the dramatic ice-shifts were too much. By the summer of 1964 more than 120 tons of snow and ice had to be trimmed and removed per month. The nuclear reactor was removed at that time, leaving only the diesel-electric power station to provide energy to the camp. Slowly they let the camp be abandoned, the last staff left in 1966.

A return visit in 1969 found the contorted, mangled remains of the buildings. Explorers observed twisted steel beams, snapped supporting timbers and a still standing building being slowly crushed under the ‘extreme pressure of the encroaching snow.’

During its short life the camp produced some of the first ice cores which provided a solid base for research into climate change and the effects of meteor and comet strike on our planet. The data stretches back over 100,000 years and is still being used to this day. That is how science goes, do new things in new places and something of use almost always turns up, even in a vast glacier. If that isn’t cool I don’t know what is.

Further Reading: